The second most important capability of Hibernate Search is the ability to execute Lucene queries and retrieve entities managed by a Hibernate session. The search provides the power of Lucene without leaving the Hibernate paradigm, giving another dimension to the Hibernate classic search mechanisms (HQL, Criteria query, native SQL query).

Preparing and executing a query consists of four simple steps:

- Creating a

FullTextSession - Creating a Lucene query either via the Hibernate Search query DSL (recommended) or by utilizing the Lucene query API

- Wrapping the Lucene query using an

org.hibernate.Query - Executing the search by calling for example

list()orscroll()

To access the querying facilities, you have to use a FullTextSession. This Search specific session

wraps a regular org.hibernate.Session in order to provide query and indexing capabilities.

Example 5.1. Creating a FullTextSession

Session session = sessionFactory.openSession();

//...

FullTextSession fullTextSession = Search.getFullTextSession(session);Once you have a FullTextSession you have two options to build the full-text query: the Hibernate

Search query DSL or the native Lucene query.

If you use the Hibernate Search query DSL, it will look like this:

QueryBuilder b = fullTextSession.getSearchFactory()

.buildQueryBuilder().forEntity(Myth.class).get();

org.apache.lucene.search.Query luceneQuery =

b.keyword()

.onField("history").boostedTo(3)

.matching("storm")

.createQuery();

org.hibernate.Query fullTextQuery = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery);

List result = fullTextQuery.list(); //return a list of managed objectsYou can alternatively write your Lucene query either using the Lucene query parser or Lucene programmatic API.

Example 5.2. Creating a Lucene query via the QueryParser

SearchFactory searchFactory = fullTextSession.getSearchFactory();

org.apache.lucene.queryparser.classic.QueryParser parser =

new QueryParser("title", searchFactory.getAnalyzer(Myth.class));

try {

org.apache.lucene.search.Query luceneQuery = parser.parse("history:storm^3");

}

catch (ParseException e) {

//handle parsing failure

}

org.hibernate.Query fullTextQuery = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery);

List result = fullTextQuery.list(); //return a list of managed objectsNote

The Hibernate query built on top of the Lucene query is a regular org.hibernate.Query, which means

you are in the same paradigm as the other Hibernate query facilities (HQL, Native or Criteria). The

regular list() , uniqueResult(), iterate() and scroll() methods can be used.

In case you are using the Java Persistence APIs of Hibernate, the same extensions exist:

Example 5.3. Creating a Search query using the JPA API

EntityManager em = entityManagerFactory.createEntityManager();

FullTextEntityManager fullTextEntityManager =

org.hibernate.search.jpa.Search.getFullTextEntityManager(em);

// ...

QueryBuilder b = fullTextEntityManager.getSearchFactory()

.buildQueryBuilder().forEntity( Myth.class ).get();

org.apache.lucene.search.Query luceneQuery =

b.keyword()

.onField("history").boostedTo(3)

.matching("storm")

.createQuery();

javax.persistence.Query fullTextQuery =

fullTextEntityManager.createFullTextQuery( luceneQuery );

List result = fullTextQuery.getResultList(); //return a list of managed objectsNote

The following examples we will use the Hibernate APIs but the same example can be easily rewritten with the Java Persistence API by just adjusting the way the FullTextQuery is retrieved.

Hibernate Search queries are built on top of Lucene queries which gives you total freedom on the type of Lucene query you want to execute. However, once built, Hibernate Search wraps further query processing using org.hibernate.Query as your primary query manipulation API.

Using the Lucene API, you have several options. You can use the query parser (fine for simple queries) or the Lucene programmatic API (for more complex use cases). It is out of the scope of this documentation on how to exactly build a Lucene query. Please refer to the online Lucene documentation or get hold of a copy of Lucene In Action or Hibernate Search in Action.

Writing full-text queries with the Lucene programmatic API is quite complex. It’s even more complex to understand the code once written. Besides the inherent API complexity, you have to remember to convert your parameters to their string equivalent as well as make sure to apply the correct analyzer to the right field (a ngram analyzer will for example use several ngrams as the tokens for a given word and should be searched as such).

The Hibernate Search query DSL makes use of a style of API called a fluent API. This API has a few key characteristics:

- it has meaningful method names making a succession of operations reads almost like English

- it limits the options offered to what makes sense in a given context (thanks to strong typing and IDE auto-completion).

- it often uses the chaining method pattern

- it’s easy to use and even easier to read

Let’s see how to use the API. You first need to create a query builder that is attached to a given

indexed entity type. This QueryBuilder will know what analyzer to use and what field bridge to

apply. You can create several QueryBuilder instances (one for each entity type involved in the root

of your query). You get the QueryBuilder from the SearchFactory.

QueryBuilder mythQB = searchFactory.buildQueryBuilder().forEntity( Myth.class ).get();You can also override the analyzer used for a given field or fields. This is rarely needed and should be avoided unless you know what you are doing.

QueryBuilder mythQB = searchFactory.buildQueryBuilder()

.forEntity( Myth.class )

.overridesForField("history","stem_analyzer_definition")

.get();Using the query builder, you can then build queries. It is important to realize that the end result of a QueryBuilder is a Lucene query. For this reason you can easily mix and match queries generated via Lucene’s query parser or Query objects you have assembled with the Lucene programmatic API and use them with the Hibernate Search DSL. Just in case the DSL is missing some features.

Let’s start with the most basic use case - searching for a specific word:

Query luceneQuery = mythQB.keyword().onField("history").matching("storm").createQuery();keyword() means that you are trying to find a specific word. onField() specifies in which Lucene

field to look. matching() tells what to look for. And finally createQuery() creates the Lucene

query object. A lot is going on with this line of code.

- The value storm is passed through the

historyFieldBridge: it does not matter here but you will see that it’s quite handy when dealing with numbers or dates. - The field bridge value is then passed to the analyzer used to index the field

history. This ensures that the query uses the same term transformation than the indexing (lower case, n-gram, stemming and so on). If the analyzing process generates several terms for a given word, a boolean query is used with theSHOULDlogic (roughly anORlogic).

We make the example a little more advanced now and have a look at how to search a field that uses ngram analyzers. ngram analyzers index succession of ngrams of your words which helps to recover from user typos. For example the 3-grams of the word hibernate are hib, ibe, ber, rna, nat, ate.

@AnalyzerDef(name = "ngram",

tokenizer = @TokenizerDef(factory = StandardTokenizerFactory.class ),

filters = {

@TokenFilterDef(factory = StandardFilterFactory.class),

@TokenFilterDef(factory = LowerCaseFilterFactory.class),

@TokenFilterDef(factory = StopFilterFactory.class),

@TokenFilterDef(factory = NGramFilterFactory.class,

params = {

@Parameter(name = "minGramSize", value = "3"),

@Parameter(name = "maxGramSize", value = "3") } )

}

)

@Entity

@Indexed

public class Myth {

@Field(analyzer=@Analyzer(definition="ngram")

public String getName() { return name; }

public String setName(String name) { this.name = name; }

private String name;

...

}

Query luceneQuery = mythQb.keyword().onField("name").matching("Sisiphus")

.createQuery();The matching word "Sisiphus" will be lower-cased and then split into 3-grams: sis, isi, sip, phu,

hus. Each of these n-gram will be part of the query. We will then be able to find the Sysiphus myth

(with a y). All that is transparently done for you.

Note

If for some reason you do not want a specific field to use the field bridge or the analyzer you can

call the ignoreAnalyzer() or ignoreFieldBridge() functions.

To search for multiple possible words in the same field, simply add them all in the matching clause.

//search document with storm or lightning in their history

Query luceneQuery =

mythQB.keyword().onField("history").matching("storm lightning").createQuery();To search the same word on multiple fields, use the onFields method.

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.keyword()

.onFields("history","description","name")

.matching("storm")

.createQuery();Sometimes, one field should be treated differently from another field even if searching the same term, you can use the andField() method for that.

Query luceneQuery = mythQB.keyword()

.onField("history")

.andField("name")

.boostedTo(5)

.andField("description")

.matching("storm")

.createQuery();In the previous example, only field name is boosted to 5.

To execute a fuzzy query (based on the Levenshtein distance algorithm), start like a keyword query

and add the fuzzy flag.

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.keyword()

.fuzzy()

.withThreshold(.8f)

.withPrefixLength(1)

.onField("history")

.matching("starm")

.createQuery();threshold is the limit above which two terms are considering matching. It’s a decimal between 0 and

1 and defaults to 0.5. prefixLength is the length of the prefix ignored by the "fuzzyness": while

it defaults to 0, a non zero value is recommended for indexes containing a huge amount of distinct

terms.

You can also execute wildcard queries (queries where some of parts of the word are unknown).

The character ? represents a single character and * represents any character sequence.

Note that for performance purposes, it is recommended that the query does not start with either ? or *.

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.keyword()

.wildcard()

.onField("history")

.matching("sto*")

.createQuery();Note

Wildcard queries do not apply the analyzer on the matching terms. Otherwise the risk of * or ?

being mangled is too high.

So far we have been looking for words or sets of words, you can also search exact or approximate

sentences. Use phrase() to do so.

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.phrase()

.onField("history")

.sentence("Thou shalt not kill")

.createQuery();You can search approximate sentences by adding a slop factor. The slop factor represents the number of other words permitted in the sentence: this works like a within or near operator

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.phrase()

.withSlop(3)

.onField("history")

.sentence("Thou kill")

.createQuery();After looking at all these query examples for searching for to a given word, it is time to introduce range queries (on numbers, dates, strings etc). A range query searches for a value in between given boundaries (included or not) or for a value below or above a given boundary (included or not).

//look for 0 <= starred < 3

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.range()

.onField("starred")

.from(0).to(3).excludeLimit()

.createQuery();

//look for myths strictly BC

Date beforeChrist = ...;

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.range()

.onField("creationDate")

.below(beforeChrist).excludeLimit()

.createQuery();This set of queries has its own chapter, check out Chapter 9, Spatial.

Important

This feature is considered experimental.

Have you ever looked at an article or document and thought: "I want to find more like this"? Have you ever appreciated an e-commerce website that gives you similar articles to the one you are exploring?

More Like This queries are achieving just that. You feed it an entity (or its identifier) and Hibernate Search returns the list of entities that are similar.

How does it work?

For each (selected) field of the targeted entity, we look at the most meaningful terms. Then we

create a query matching the most meaningful terms per field. This is a slight variation compared to

the original Lucene MoreLikeThisQuery implementation.

The query DSL API should be self explaining. Let’s look at some usage examples.

QueryBuilder qb = fullTextSession.getSearchFactory()

.buildQueryBuilder()

.forEntity( Coffee.class )

.get();

Query mltQuery = qb

.moreLikeThis()

.comparingAllFields()

.toEntityWithId( coffeeId )

.createQuery();

List<Object[]> results = (List<Object[]>) fullTextSession

.createFullTextQuery( mltQuery, Coffee.class )

.setProjection( ProjectionConstants.THIS, ProjectionConstants.SCORE )

.list();This first example takes the id of an Coffee entity and finds the matching coffees across all fields. To be fair, this is not across all fields. To be included in the More Like This query, fields need to store term vectors or the actual field value. Id fields (of the root entity as well as embedded entities) and numeric fields are excluded. The latter exclusion might change in future versions.

Looking at the Coffee class, the following fields are considered: name as it is stored,

description as it stores the term vector. id and internalDescription are excluded.

@Entity @Indexed

public class Coffee {

@Id @GeneratedValue

public Integer getId() { return id; }

@Field(termVector = TermVector.NO, store = Store.YES)

public String getName() { return name; }

@Field(termVector = TermVector.YES)

public String getSummary() { return summary; }

@Column(length = 2000)

@Field(termVector = TermVector.YES)

public String getDescription() { return description; }

public int getIntensity() { return intensity; }

// Not stored nor term vector, i.e. cannot be used for More Like This

@Field

public String getInternalDescription() { return internalDescription; }

// ...

}In the example above we used projection to retrieve the relative score of each element. We might use the score to only display the results for which the score is high enough.

Tip

For best performance and best results, store the term vectors for the fields you want to include in a More Like This query.

Often, you are only interested in a few key fields to find similar entities. Plus some fields are more important than others and should be boosted.

Query mltQuery = qb

.moreLikeThis()

.comparingField("summary").boostedTo(10f)

.andField("description")

.toEntityWithId( coffeeId )

.createQuery();In this example, we look for similar entities by summary and description. But similar summaries are more important than similar descriptions. This is a critical tool to make More Like This meaningful for your data set.

Instead of providing the entity id, you can pass the full entity object. If the entity contains the identifier, we will use it to find the term vectors or field values. This means that we will compare the entity state as stored in the Lucene index. If the identifier cannot be retrieved (for example if the entity has not been persisted yet), we will look at each of the entity properties to find the most meaningful terms. The latter is slower and won’t give the best results - avoid it if possible.

Here is how you pass the entity instance you want to compare with:

Coffee coffee = ...; //managed entity from somewhere

Query mltQuery = qb

.moreLikeThis()

.comparingField("summary").boostedTo(10f)

.andField("description")

.toEntity( coffee )

.createQuery();Note

By default, the results contain at the top the entity you are comparing with. This is particularly useful to compare relative scores. If you don’t need it, you can exclude it.

Query mltQuery = qb

.moreLikeThis()

.excludeEntityUsedForComparison()

.comparingField("summary").boostedTo(10f)

.andField("description")

.toEntity( coffee )

.createQuery();You can ask Hibernate Search to give a higher score to the very similar entities and downgrade the

score of mildly similar entities. We do that by boosting each meaningful terms by their individual

overall score. Start with a boost factor of 1 and adjust from there.

Query mltQuery = qb

.moreLikeThis()

.favorSignificantTermsWithFactor(1f)

.comparingField("summary").boostedTo(10f)

.andField("description")

.toEntity( coffee )

.createQuery();Remember, more like this is a very subjective meaning and will vary depending on your data and the rules of your domain. With the various options offered, Hibernate Search arms you with the tools to adjust this weapon. Make sure to continuously test the results against your data set.

Finally, you can aggregate (combine) queries to create more complex queries. The following aggregation operators are available:

SHOULD: the query query should contain the matching elements of the subqueryMUST: the query must contain the matching elements of the subqueryMUST NOT: the query must not contain the matching elements of the subquery

The sub-queries can be any Lucene query including a boolean query itself. Let’s look at a few examples:

//look for popular modern myths that are not urban

Date twentiethCentury = ...;

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.bool()

.must( mythQB.keyword().onField("description").matching("urban").createQuery() )

.not()

.must( mythQB.range().onField("starred").above(4).createQuery() )

.must( mythQB

.range()

.onField("creationDate")

.above(twentiethCentury)

.createQuery() )

.createQuery();

//look for popular myths that are preferably urban

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.bool()

.should( mythQB.keyword().onField("description").matching("urban").createQuery() )

.must( mythQB.range().onField("starred").above(4).createQuery() )

.createQuery();

//look for all myths except religious ones

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.all()

.except( monthQb

.keyword()

.onField( "description_stem" )

.matching( "religion" )

.createQuery()

)

.createQuery();We already have seen several query options in the previous example, but lets summarize again the options for query types and fields:

boostedTo(on query type and on field): boost the whole query or the specific field to a given factorwithConstantScore(on query): all results matching the query have a constant score equals to the boostfilteredBy(Filter)(on query): filter query results using the Filter instanceignoreAnalyzer(on field): ignore the analyzer when processing this fieldignoreFieldBridge(on field): ignore field bridge when processing this field

Let’s check out an example using some of these options

Query luceneQuery = mythQB

.bool()

.should( mythQB.keyword().onField("description").matching("urban").createQuery() )

.should( mythQB

.keyword()

.onField("name")

.boostedTo(3)

.ignoreAnalyzer()

.matching("urban").createQuery() )

.must( mythQB

.range()

.boostedTo(5).withConstantScore()

.onField("starred").above(4).createQuery() )

.createQuery();As you can see, the Hibernate Search query DSL is an easy to use and easy to read query API and by accepting and producing Lucene queries, you can easily incorporate query types not (yet) supported by the DSL. Please give us feedback!

So far we only covered the process of how to create your Lucene query (see Section 5.1, “Building queries”). However, this is only the first step in the chain of actions. Let’s now see how to build the Hibernate Search query from the Lucene query.

Once the Lucene query is built, it needs to be wrapped into an Hibernate Query. If not specified otherwise, the query will be executed against all indexed entities, potentially returning all types of indexed classes.

Example 5.4. Wrapping a Lucene query into a Hibernate Query

FullTextSession fullTextSession = Search.getFullTextSession( session );

org.hibernate.Query fullTextQuery = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery( luceneQuery );It is advised, from a performance point of view, to restrict the returned types:

Example 5.5. Filtering the search result by entity type

fullTextQuery = fullTextSession

.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Customer.class);

// or

fullTextQuery = fullTextSession

.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Item.class, Actor.class);In Example 5.5, “Filtering the search result by entity type” the first example returns only matching Customer instances,

the second returns matching Actor and Item instances. The type restriction is fully polymorphic

which means that if there are two indexed subclasses Salesman and Customer of the baseclass

Person, it is possible to just specify Person.class in order to filter on result types.

Out of performance reasons it is recommended to restrict the number of returned objects per query. In fact is a very common use case anyway that the user navigates from one page to an other. The way to define pagination is exactly the way you would define pagination in a plain HQL or Criteria query.

Example 5.6. Defining pagination for a search query

org.hibernate.Query fullTextQuery =

fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Customer.class);

fullTextQuery.setFirstResult(15); //start from the 15th element

fullTextQuery.setMaxResults(10); //return 10 elementsTip

It is still possible to get the total number of matching elements regardless of the pagination via fulltextQuery.getResultSize()

Apache Lucene provides a very flexible and powerful way to sort results. While the default sorting (by relevance) is appropriate most of the time, it can be interesting to sort by one or several other properties. In order to do so set the Lucene Sort object to apply a Lucene sorting strategy.

Example 5.7. Specifying a Lucene Sort in order to sort the result

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query = s.createFullTextQuery( query, Book.class );

org.apache.lucene.search.Sort sort = new Sort(

new SortField("title", SortField.STRING));

query.setSort(sort);

List results = query.list();Tip

Be aware that fields used for sorting must not be tokenized (see Section 4.1.1.2, “@Field”).

When you restrict the return types to one class, Hibernate Search loads the objects using a single query. It also respects the static fetching strategy defined in your domain model.

It is often useful, however, to refine the fetching strategy for a specific use case.

Example 5.8. Specifying FetchMode on a query

Criteria criteria =

s.createCriteria(Book.class).setFetchMode("authors", FetchMode.JOIN);

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery).setCriteriaQuery(criteria);In this example, the query will return all Books matching the luceneQuery. The authors collection will be loaded from the same query using an SQL outer join.

When defining a criteria query, it is not necessary to restrict the returned entity types when creating the Hibernate Search query from the full text session: the type is guessed from the criteria query itself.

Important

Only fetch mode can be adjusted, refrain from applying any other restriction. While it is known to

work as of Hibernate Search 4, using restriction (ie a where clause) on your Criteria query should

be avoided when possible. getResultSize() will throw a SearchException if used in conjunction with a

Criteria with restriction.

Important

You cannot use setCriteriaQuery if more than one entity type is expected to be returned.

For some use cases, returning the domain object (including its associations) is overkill. Only a small subset of the properties is necessary. Hibernate Search allows you to return a subset of properties:

Example 5.9. Using projection instead of returning the full domain object

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query =

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Book.class);

setProjection("id", "summary", "body", "mainAuthor.name");

List results = query.list();

Object[] firstResult = (Object[]) results.get(0);

Integer id = firstResult[0];

String summary = firstResult[1];

String body = firstResult[2];

String authorName = firstResult[3];Hibernate Search extracts the properties from the Lucene index and convert them back to their object

representation, returning a list of Object[]. Projections avoid a potential database round trip

(useful if the query response time is critical). However, it also has several constraints:

- the properties projected must be stored in the index (

@Field(store=Store.YES)), which increases the index size - the properties projected must use a

FieldBridgeimplementing org.hibernate.search.bridge.TwoWayFieldBridge ororg.hibernate.search.bridge.TwoWayStringBridge, the latter being the simpler version.

Note

All Hibernate Search built-in types are two-way.

- you can only project simple properties of the indexed entity or its embedded associations. This means you cannot project a whole embedded entity.

- projection does not work on collections or maps which are indexed via

@IndexedEmbedded

Projection is also useful for another kind of use case. Lucene can provide metadata information about the results. By using some special projection constants, the projection mechanism can retrieve this metadata:

Example 5.10. Using projection in order to retrieve meta data

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query =

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Book.class);

query.setProjection(

FullTextQuery.SCORE,

FullTextQuery.THIS,

"mainAuthor.name" );

List results = query.list();

Object[] firstResult = (Object[]) results.get(0);

float score = firstResult[0];

Book book = firstResult[1];

String authorName = firstResult[2];You can mix and match regular fields and projection constants. Here is the list of the available constants:

FullTextQuery.THIS: returns the initialized and managed entity (as a non projected query would have done).FullTextQuery.DOCUMENT: returns the Lucene Document related to the object projected.FullTextQuery.OBJECT_CLASS: returns the class of the indexed entity.FullTextQuery.SCORE: returns the document score in the query. Scores are handy to compare one result against an other for a given query but are useless when comparing the result of different queries.FullTextQuery.ID: the id property value of the projected object.FullTextQuery.DOCUMENT_ID: the Lucene document id. Careful, Lucene document id can change overtime between two different IndexReader opening.FullTextQuery.EXPLANATION: returns the Lucene Explanation object for the matching object/document in the given query. Do not use if you retrieve a lot of data. Running explanation typically is as costly as running the whole Lucene query per matching element. Make sure you use projection!

By default, Hibernate Search uses the most appropriate strategy to initialize entities matching your full text query. It executes one (or several) queries to retrieve the required entities. This is the best approach to minimize database round trips in a scenario where none / few of the retrieved entities are present in the persistence context (ie the session) or the second level cache.

If most of your entities are present in the second level cache, you can force Hibernate Search to look into the cache before retrieving an object from the database.

Example 5.11. Check the second-level cache before using a query

FullTextQuery query = session.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, User.class);

query.initializeObjectWith(

ObjectLookupMethod.SECOND_LEVEL_CACHE,

DatabaseRetrievalMethod.QUERY

);ObjectLookupMethod defines the strategy used to check if an object is easily accessible (without

database round trip). Other options are:

ObjectLookupMethod.PERSISTENCE_CONTEXT: useful if most of the matching entities are already in the persistence context (ie loaded in the Session or EntityManager)ObjectLookupMethod.SECOND_LEVEL_CACHE: check first the persistence context and then the second-level cache.

Note

Note that to search in the second-level cache, several settings must be in place:

- the second level cache must be properly configured and active

- the entity must have enabled second-level cache (eg via

@Cacheable) - the

Session,EntityManagerorQuerymust allow access to the second-level cache for read access (ieCacheMode.NORMALin Hibernate native APIs orCacheRetrieveMode.USEin JPA 2 APIs).

Warning

Avoid using ObjectLookupMethod.SECOND_LEVEL_CACHE unless your second level cache

implementation is either EHCache or Infinispan; other second level cache providers don’t currently

implement this operation efficiently.

You can also customize how objects are loaded from the database (if not found before). Use

DatabaseRetrievalMethod for that:

QUERY(default): use a (set of) queries to load several objects in batch. This is usually the best approach.FIND_BY_ID: load objects one by one using theSession.getorEntityManager.findsemantic. This might be useful if batch-size is set on the entity (in which case, entities will be loaded in batch by Hibernate Core). QUERY should be preferred almost all the time.

The defaults for both methods, the object lookup as well as the database retrieval can also be

configured via configuration properties. This way you don’t have to specify your preferred methods on

each query creation. The property names are hibernate.search.query.object_lookup_method

and hibernate.search.query.database_retrieval_method respectively. As value use the name of the

method (upper- or lowercase). For example:

Example 5.12. Setting object lookup and database retrieval methods via configuration properties

hibernate.search.query.object_lookup_method = second_level_cache hibernate.search.query.database_retrieval_method = query

You can limit the time a query takes in Hibernate Search in two ways:

- raise an exception when the limit is reached

- limit to the number of results retrieved when the time limit is raised

You can decide to stop a query if when it takes more than a predefined amount of time. Note that this is a best effort basis but if Hibernate Search still has significant work to do and if we are beyond the time limit, a QueryTimeoutException will be raised (org.hibernate.QueryTimeoutException or javax.persistence.QueryTimeoutException depending on your programmatic API).

To define the limit when using the native Hibernate APIs, use one of the following approaches

Example 5.13. Defining a timeout in query execution

Query luceneQuery = ...;

FullTextQuery query = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, User.class);

//define the timeout in seconds

query.setTimeout(5);

//alternatively, define the timeout in any given time unit

query.setTimeout(450, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

try {

query.list();

}

catch (org.hibernate.QueryTimeoutException e) {

//do something, too slow

}Likewise getResultSize(), iterate() and scroll() honor the timeout but only until the end of

the method call. That simply means that the methods of Iterable or the ScrollableResults ignore the

timeout.

Note

explain() does not honor the timeout: this method is used for debug purposes and in particular to find out why a query is slow

When using JPA, simply use the standard way of limiting query execution time.

Example 5.14. Defining a timeout in query execution

Query luceneQuery = ...;

FullTextQuery query = fullTextEM.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, User.class);

//define the timeout in milliseconds

query.setHint( "javax.persistence.query.timeout", 450 );

try {

query.getResultList();

}

catch (javax.persistence.QueryTimeoutException e) {

//do something, too slow

}Important

Remember, this is a best effort approach and does not guarantee to stop exactly on the specified timeout.

Alternatively, you can return the number of results which have already been fetched by the time the limit is reached. Note that only the Lucene part of the query is influenced by this limit. It is possible that, if you retrieve managed object, it takes longer to fetch these objects.

Warning

This approach is not compatible with the setTimeout approach.

To define this soft limit, use the following approach

Example 5.15. Defining a time limit in query execution

Query luceneQuery = ...;

FullTextQuery query = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, User.class);

//define the timeout in seconds

query.limitExecutionTimeTo(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

List results = query.list();Likewise getResultSize(), iterate() and scroll() honor the time limit but only until the end

of the method call. That simply means that the methods of Iterable or the ScrollableResults ignore

the timeout.

You can determine if the results have been partially loaded by invoking the hasPartialResults

method.

Example 5.16. Determines when a query returns partial results

Query luceneQuery = ...;

FullTextQuery query = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, User.class);

//define the timeout in seconds

query.limitExecutionTimeTo(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

List results = query.list();

if ( query.hasPartialResults() ) {

displayWarningToUser();

}If you use the JPA API, limitExecutionTimeTo and hasPartialResults are also available to you.

Once the Hibernate Search query is built, executing it is in no way different than executing a HQL

or Criteria query. The same paradigm and object semantic applies. All the common operations are

available: list(), uniqueResult(), iterate(), scroll().

If you expect a reasonable number of results (for example using pagination) and expect to work on

all of them, list() or uniqueResult() are recommended. list() work best if the entity batch-size

is set up properly. Note that Hibernate Search has to process all Lucene Hits elements (within the

pagination) when using list() , uniqueResult() and iterate().

If you wish to minimize Lucene document loading, scroll() is more appropriate. Don’t forget to close

the ScrollableResults object when you’re done, since it keeps Lucene resources. If you expect to use

scroll, but wish to load objects in batch, you can use query.setFetchSize(). When an object is

accessed, and if not already loaded, Hibernate Search will load the next fetchSize objects in one

pass.

Important

Pagination is preferred over scrolling.

It is sometimes useful to know the total number of matching documents:

- for the Google-like feature "1-10 of about 888,000,000"

- to implement a fast pagination navigation

- to implement a multi step search engine (adding approximation if the restricted query return no or not enough results)

Of course it would be too costly to retrieve all the matching documents. Hibernate Search allows you to retrieve the total number of matching documents regardless of the pagination parameters. Even more interesting, you can retrieve the number of matching elements without triggering a single object load.

Example 5.17. Determining the result size of a query

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query =

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Book.class);

//return the number of matching books without loading a single one

assert 3245 == query.getResultSize();

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query =

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Book.class);

query.setMaxResult(10);

List results = query.list();

//return the total number of matching books regardless of pagination

assert 3245 == query.getResultSize();Note

Like Google, the number of results is an approximation if the index is not fully up-to-date with the database (asynchronous cluster for example).

As seen in Section 5.1.3.5, “Projection” projection results are returns as Object arrays. This data structure is not always matching the application needs. In this cases It is possible to apply a ResultTransformer which post query execution can build the needed data structure:

Example 5.18. Using ResultTransformer in conjunction with projections

org.hibernate.search.FullTextQuery query =

s.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Book.class);

query.setProjection("title", "mainAuthor.name");

query.setResultTransformer(

new StaticAliasToBeanResultTransformer(

BookView.class,

"title",

"author" )

);

ListBookView>; results = (List<BookView>) query.list();

for (BookView view : results) {

log.info("Book: " + view.getTitle() + ", " + view.getAuthor());

}Examples of ResultTransformer implementations can be found in the Hibernate Core codebase.

You will find yourself sometimes puzzled by a result showing up in a query or a result not showing up in a query. Luke is a great tool to understand those mysteries. However, Hibernate Search also gives you access to the Lucene Explanation object for a given result (in a given query). This class is considered fairly advanced to Lucene users but can provide a good understanding of the scoring of an object. You have two ways to access the Explanation object for a given result:

- Use the fullTextQuery.explain(int) method

- Use projection

The first approach takes a document id as a parameter and return the Explanation object. The

document id can be retrieved using projection and the FullTextQuery.DOCUMENT_ID constant.

Warning

The Document id has nothing to do with the entity id. Do not mess up these two notions.

In the second approach you project the Explanation object using the FullTextQuery.EXPLANATION

constant.

Example 5.19. Retrieving the Lucene Explanation object using projection

FullTextQuery ftQuery = s.createFullTextQuery( luceneQuery, Dvd.class )

.setProjection(

FullTextQuery.DOCUMENT_ID,

FullTextQuery.EXPLANATION,

FullTextQuery.THIS );

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked") List<Object[]> results = ftQuery.list();

for (Object[] result : results) {

Explanation e = (Explanation) result[1];

display( e.toString() );

}Be careful, building the explanation object is quite expensive, it is roughly as expensive as running the Lucene query again. Don’t do it if you don’t need the object

Apache Lucene has a powerful feature that allows to filter query results according to a custom filtering process. This is a very powerful way to apply additional data restrictions, especially since filters can be cached and reused. Some interesting use cases are:

- security

- temporal data (eg. view only last month’s data)

- population filter (eg. search limited to a given category)

- and many more

Hibernate Search pushes the concept further by introducing the notion of parameterizable named filters which are transparently cached. For people familiar with the notion of Hibernate Core filters, the API is very similar:

Example 5.20. Enabling fulltext filters for a given query

fullTextQuery = s.createFullTextQuery(query, Driver.class);

fullTextQuery.enableFullTextFilter("bestDriver");

fullTextQuery.enableFullTextFilter("security").setParameter("login", "andre");

fullTextQuery.list(); //returns only best drivers where andre has credentialsIn this example we enabled two filters on top of the query. You can enable (or disable) as many filters as you like.

Declaring filters is done through the @FullTextFilterDef annotation.

You can use @FullTextFilterDef or @FullTextFilterDefs on any:

*@Indexed entity regardless of the query the filter is later applied to

* Parent class of an @Indexed entity

* package-info.java of a package containing an @Indexed entity

This implies that filter definitions are global and their names must be unique.

A SearchException is thrown in case two different @FullTextFilterDef annotations

with the same name are defined. Each named filter has to

specify its actual filter implementation.

Example 5.21. Defining and implementing a Filter

@Entity

@Indexed

@FullTextFilterDefs( {

@FullTextFilterDef(name = "bestDriver", impl = BestDriversFilter.class),

@FullTextFilterDef(name = "security", impl = SecurityFilterFactory.class)

})

public class Driver { ... }public class BestDriversFilter extends org.apache.lucene.search.Filter {

public DocIdSet getDocIdSet(IndexReader reader) throws IOException {

OpenBitSet bitSet = new OpenBitSet( reader.maxDoc() );

TermDocs termDocs = reader.termDocs( new Term( "score", "5" ) );

while ( termDocs.next() ) {

bitSet.set( termDocs.doc() );

}

return bitSet;

}

}BestDriversFilter is an example of a simple Lucene filter which reduces the result set to drivers

whose score is 5. In this example the specified filter implements the

org.apache.lucene.search.Filter directly and contains a no-arg constructor.

If your Filter creation requires additional steps or if the filter you want to use does not have a no-arg constructor, you can use the factory pattern:

Example 5.22. Creating a filter using the factory pattern

@Entity

@Indexed

@FullTextFilterDef(name = "bestDriver", impl = BestDriversFilterFactory.class)

public class Driver { ... }

public class BestDriversFilterFactory {

@Factory

public Filter getFilter() {

//some additional steps to cache the filter results per IndexReader

Filter bestDriversFilter = new BestDriversFilter();

return new CachingWrapperFilter(bestDriversFilter);

}

}Hibernate Search will look for a @Factory annotated method and use it to build the filter

instance. The factory must have a no-arg constructor.

Named filters come in handy where parameters have to be passed to the filter. For example a security filter might want to know which security level you want to apply:

Example 5.23. Passing parameters to a defined filter

fullTextQuery = s.createFullTextQuery(query, Driver.class);

fullTextQuery.enableFullTextFilter("security").setParameter("level", 5);Each parameter must have an associated setter on either the filter or filter factory of the targeted named filter definition.

Example 5.24. Using parameters in the actual filter implementation

public class SecurityFilterFactory {

private Integer level;

/**

* injected parameter

*/

public void setLevel(Integer level) {

this.level = level;

}

@Factory

public Filter getFilter() {

Query query = new TermQuery( new Term( "level", level.toString() ) );

return new CachingWrapperFilter( new QueryWrapperFilter(query) );

}

}Filters will be cached once created, based on all their parameter names and values.

Caching happens using a combination of

hard and soft references to allow disposal of memory when needed. The hard reference cache keeps

track of the most recently used filters and transforms the ones least used to SoftReferences when

needed. Once the limit of the hard reference cache is reached additional filters are cached as

SoftReferences. To adjust the size of the hard reference cache, use

hibernate.search.filter.cache_strategy.size (defaults to 128). For advanced use of filter

caching, you can implement your own FilterCachingStrategy. The classname is defined by

hibernate.search.filter.cache_strategy.

This filter caching mechanism should not be confused with caching the actual filter results. In

Lucene it is common practice to wrap filters using the IndexReader around a CachingWrapperFilter.

The wrapper will cache the DocIdSet returned from the getDocIdSet(IndexReader reader) method to

avoid expensive re-computation. It is important to mention that the computed DocIdSet is only

cachable for the same IndexReader instance, because the reader effectively represents the state of

the index at the moment it was opened. The document list cannot change within an opened

IndexReader. A different/new IndexReader instance, however, works potentially on a different set

of Documents (either from a different index or simply because the index has changed), hence the

cached DocIdSet has to be recomputed.

Hibernate Search also helps with this aspect of caching. Per default the cache flag of

@FullTextFilterDef is set to FilterCacheModeType.INSTANCE_AND_DOCIDSETRESULTS which will

automatically cache the filter instance as well as wrap the specified filter around a Hibernate

specific implementation of CachingWrapperFilter. In contrast to Lucene’s version of this class

SoftReferences are used together with a hard reference count (see discussion about filter cache).

The hard reference count can be adjusted using hibernate.search.filter.cache_docidresults.size

(defaults to 5). The wrapping behavior can be controlled using the @FullTextFilterDef.cache

parameter. There are three different values for this parameter:

| Value | Definition |

|---|---|

FilterCacheModeType.NONE | No filter instance and no result is cached by Hibernate Search. For every filter call, a new filter instance is created. This setting might be useful for rapidly changing data sets or heavily memory constrained environments. |

FilterCacheModeType.INSTANCE_ONLY | The filter instance is cached and reused across concurrent Filter.getDocIdSet() calls. DocIdSet results are not cached. This setting is useful when a filter uses its own specific caching mechanism or the filter results change dynamically due to application specific events making DocIdSet caching in both cases unnecessary. |

FilterCacheModeType.INSTANCE_AND_DOCIDSETRESULTS | Both the filter instance and the DocIdSet results are cached. This is the default value. |

Last but not least - why should filters be cached? There are two areas where filter caching shines:

- the system does not update the targeted entity index often (in other words, the IndexReader is reused a lot)

- the Filter’s DocIdSet is expensive to compute (compared to the time spent to execute the query)

It is possible, in a sharded environment to execute queries on a subset of the available shards. This can be done in two steps:

- create a sharding strategy that does select a subset of IndexManagers depending on some filter configuration

- activate the proper filter at query time

Let’s first look at an example of sharding strategy that query on a specific customer shard if the customer filter is activated.

public class CustomerShardingStrategy implements IndexShardingStrategy {

// stored IndexManagers in a array indexed by customerID

private IndexManager[] indexManagers;

public void initialize(Properties properties, IndexManager[] indexManagers) {

this.indexManagers = indexManagers;

}

public IndexManager[] getIndexManagersForAllShards() {

return indexManagers;

}

public IndexManager getIndexManagerForAddition(

Class<?> entity, Serializable id, String idInString, Document document) {

Integer customerID = Integer.parseInt(document.getFieldable("customerID").stringValue());

return indexManagers[customerID];

}

public IndexManager[] getIndexManagersForDeletion(

Class<?> entity, Serializable id, String idInString) {

return getIndexManagersForAllShards();

}

/**

* Optimization; don't search ALL shards and union the results; in this case, we

* can be certain that all the data for a particular customer Filter is in a single

* shard; simply return that shard by customerID.

*/

public IndexManager[] getIndexManagersForQuery(

FullTextFilterImplementor[] filters) {

FullTextFilter filter = getCustomerFilter(filters, "customer");

if (filter == null) {

return getIndexManagersForAllShards();

}

else {

return new IndexManager[] { indexManagers[Integer.parseInt(

filter.getParameter("customerID").toString())] };

}

}

private FullTextFilter getCustomerFilter(FullTextFilterImplementor[] filters, String name) {

for (FullTextFilterImplementor filter: filters) {

if (filter.getName().equals(name)) return filter;

}

return null;

}

}In this example, if the filter named customer is present, we make sure to only use the shard

dedicated to this customer. Otherwise, we return all shards. A given Sharding strategy can react to

one or more filters and depends on their parameters.

The second step is simply to activate the filter at query time. While the filter can be a regular

filter (as defined in Section 5.3, “Filters”) which also filters Lucene results after the query, you can

make use of a special filter that will only be passed to the sharding strategy and otherwise ignored

for the rest of the query. Simply use the ShardSensitiveOnlyFilter class when declaring your filter.

@Entity @Indexed

@FullTextFilterDef(name="customer", impl=ShardSensitiveOnlyFilter.class)

public class Customer {

// ...

}FullTextQuery query = ftEm.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Customer.class);

query.enableFulltextFilter("customer").setParameter("CustomerID", 5);

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

List<Customer> results = query.getResultList();Note that by using the ShardSensitiveOnlyFilter, you do not have to implement any Lucene filter.

Using filters and sharding strategy reacting to these filters is recommended to speed up queries in

a sharded environment.

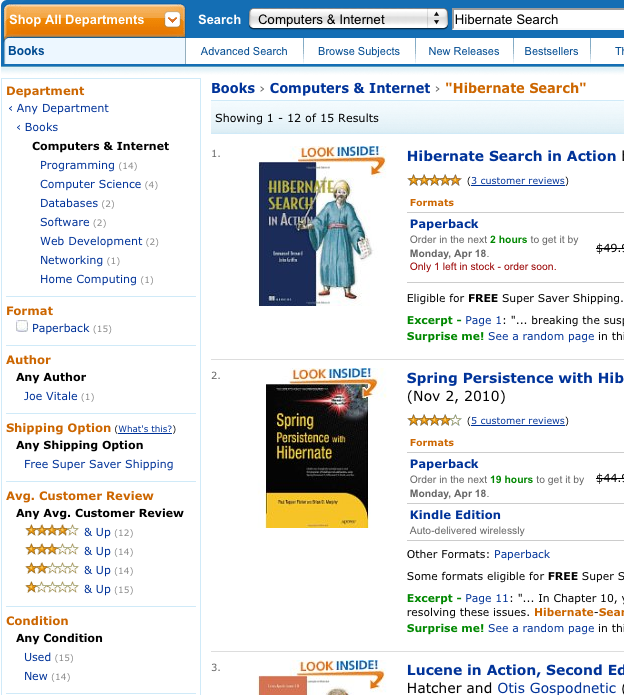

Faceted search is a technique which allows to divide the results of a query into multiple categories. This categorization includes the calculation of hit counts for each category and the ability to further restrict search results based on these facets (categories). Figure 5.1, “Facets Example on Amazon” shows a faceting example. The search for 'Hibernate Search' results in fifteen hits which are displayed on the main part of the page. The navigation bar on the left, however, shows the categoryComputers & Internet with its subcategories Programming, Computer Science, Databases, Software, Web Development, Networking and Home Computing. For each of these subcategories the number of books is shown matching the main search criteria and belonging to the respective subcategory. This division of the category Computers & Internet is one facet of this search. Another one is for example the average customer review rating.

In Hibernate Search the classes QueryBuilder and FullTextQuery are the entry point to the faceting

API. The former allows to create faceting requests whereas the latter gives access to the so called

FacetManager. With the help of the FacetManager faceting requests can be applied on a query and

selected facets can be added to an existing query in order to refine search results. The following

sections will describe the faceting process in more detail. The examples will use the entity Cd as

shown in Example 5.25, “Example entity for faceting”:

Example 5.25. Example entity for faceting

@Entity

@Indexed

public class Cd {

@Id

@GeneratedValue

private int id;

@Field,

private String name;

@Field(analyze = Analyze.NO)

@Facet

private int price;

@Field(analyze = Analyze.NO)

@DateBridge(resolution = Resolution.YEAR)

@Facet

private Date releaseYear;

@Field(analyze = Analyze.NO)

@Facet

private String label;

// setter/getter

// ...In order to facet on a given indexed field, the field needs to be configured with the @Facet

annotation. Also, the field itself cannot be analyzed.

@Facet contains a name and forField parameter. The name is arbitrary and used to identify

the facet. Per default it matches the field name it belongs to. forField is relevant in case the

property is mapped to multiple fields using @Fields (see also Section 4.1.2, “Mapping properties multiple times”). In this case

forField can be used to identify the index field to which it applies. Mirroring @Fields there

also exists a @Facets annotation in case multiple fields need to be targeted by faceting.

Last but not least, @Facet contains a

encoding parameter. Usually, Hibernate Search automatically selects the encoding:

- String fields are encoded as

FacetEncodingType.STRING byte,short,int,long(including corresponding wrapper types) andDateasFacetEncodingType.LONG- and

floatanddouble(including corresponding wrapper types) as FacetEncodingType.DOUBLE`

In some cases it can make sense, however, to explicitly set the encoding.

Discrete faceting requests for example only work for string encoded

facets. In order to use a discrete facet for numbers the encoding must be explicitly set to

FacetEncodingType.STRING.

Note

Pre Hibernate Search 5.2 there was no need to explicitly use a @Facet annotation. In 5.2 it became

necessary in order to use Lucene’s native faceting API.

The first step towards a faceted search is to create the FacetingRequest. Currently two types of

faceting requests are supported. The first type is called discrete faceting and the second type

range faceting request.

In the case of a discrete faceting request, you start with giving the request a unique name. This name will later be used to retrieve the facet values (see Section 5.4.4, “Interpreting a Facet result”). Then you need to specify on which index field you want to categorize on and which faceting options to apply. An example for a discrete faceting request can be seen in Example 5.26, “Creating a discrete faceting request”:

Example 5.26. Creating a discrete faceting request

QueryBuilder builder = fullTextSession.getSearchFactory()

.buildQueryBuilder().forEntity(Cd.class).get();

FacetingRequest labelFacetingRequest = builder.facet()

.name("labelFacetRequest")

.onField("label")

.discrete()

.orderedBy(FacetSortOrder.COUNT_DESC)

.includeZeroCounts(false)

.maxFacetCount(3)

.createFacetingRequest();When executing this faceting request a Facet instance will be created for each discrete value for

the indexed field label. The Facet instance will record the actual field value including how often

this particular field value occurs within the original query results. Parameters orderedBy,

includeZeroCounts and maxFacetCount are optional and can be applied on any faceting request.

Parameter orderedBy allows to specify in which order the created facets will be returned. The

default is FacetSortOrder.COUNT_DESC, but you can also sort on the field value. Parameter

includeZeroCount determines whether facets with a count of 0 will be included in the result (by

default they are not) and maxFacetCount allows to limit the maximum amount of facets returned.

Note

There are several preconditions an indexed field has to meet in order to categorize (facet) on it:

- The indexed property must be of type

String,Dateor of the numeric type byte, shirt, int, long, double or float (or their respective Java wrapper types). - The property has to be indexed with Analyze.NO.

- null values should be avoided.

When you need conflicting options, we suggest to index the property twice and use the appropriate field depending on the use case:

@Fields({

@Field(name="price"),

@Field(name="price_facet",

analyze=Analyze.NO,

bridge=@FieldBridge(impl = IntegerBridge.class))

})

private int price;The creation of a range faceting request is similar. We also start with a name for the request and

the field to facet on. Then we have to specify ranges for the field values. A range faceting request

can be seen in Example 5.27, “Creating a range faceting request”. There, three different price ranges are specified. below

and above can only be specified once, but you can specify as many from - to ranges as you want.

For each range boundary you can also specify via excludeLimit whether it is included into the range

or not.

Example 5.27. Creating a range faceting request

QueryBuilder builder = fullTextSession.getSearchFactory()

.buildQueryBuilder()

.forEntity(Cd.class)

.get();

FacetingRequest priceFacetingRequest = builder.facet()

.name("priceFaceting")

.onField("price_facet")

.range()

.below(1000)

.from(1001).to(1500)

.above(1500).excludeLimit()

.createFacetingRequest();The result of applying a faceting request is a list of Facet instances as seen in

Example 5.28, “Applying a faceting request”. The order within the list is given by the FacetSortOrder parameter

specified via orderedBy when creating the faceting request. The default value is

FacetSortOrder.COUNT_DESC, meaning facets are ordered by their count in descending order (highest

count first). Other values are COUNT_ASC, FIELD_VALUE and RANGE_DEFINITION_ORDER. COUNT_ASC

returns the facets in ascending count order whereas FIELD_VALUE will return them in alphabetical

order of the facet/category value (see Section 5.4.4, “Interpreting a Facet result”).

RANGE_DEFINITION_ORDER only applies for range faceting request and returns the facets in the same

order in which the ranges are defined. For Example 5.27, “Creating a range faceting request” this would mean the facet for

the range of below 1000 would be returned first, followed by the facet for the range 1001 to 1500

and finally the facet for above 1500.

In Section 5.4.1, “Creating a faceting request” we have seen how to create a faceting request. Now it is

time to apply it on a query. The key is the FacetManager which can be retrieved via the

FullTextQuery (see Example 5.28, “Applying a faceting request”).

Example 5.28. Applying a faceting request

// create a fulltext query

Query luceneQuery = builder.all().createQuery(); // match all query

FullTextQuery fullTextQuery = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery(luceneQuery, Cd.class);

// retrieve facet manager and apply faceting request

FacetManager facetManager = fullTextQuery.getFacetManager();

facetManager.enableFaceting(priceFacetingRequest);

// get the list of Cds

List<Cd> cds = fullTextQuery.list();

...

// retrieve the faceting results

List<Facet> facets = facetManager.getFacets("priceFaceting");

...You need to enable the faceting request before you execute the query. You do that via

facetManager.enableFaceting(<facetName>). You can enable as many faceting requests as you

like. Then you execute the query and retrieve the facet results for a given request via

facetManager.getFacets(<facetname>). For each request you will get a list of Facet instances.

Facet requests stay active and get applied to the fulltext query until they are either explicitly

disabled via disableFaceting(<facetName>) or the query is discarded.

Each facet request results in a list of Facet instances. Each instance represents one facet/category

value. In the CD example (Example 5.26, “Creating a discrete faceting request”) where we want to categorize on the CD

labels, there would for example be a Facet for each of the record labels Universal, Sony and Warner.

Example 5.29, “Facet API” shows the API of Facet.

Example 5.29. Facet API

public interface Facet {

/**

* @return the faceting name this {@code Facet} belongs to.

*

* @see org.hibernate.search.query.facet.FacetingRequest#getFacetingName()

*/

String getFacetingName();

/**

* Return the {@code Document} field name this facet is targeting.

* The field needs to be indexed with {@code Analyze.NO}.

*

* @return the {@code Document} field name this facet is targeting.

*/

String getFieldName();

/**

* @return the value of this facet. In case of a discrete facet it is the actual

* {@code Document} field value. In case of a range query the value is a

* string representation of the range.

*/

String getValue();

/**

* @return the facet count.

*/

int getCount();

/**

* @return a Lucene {@link Query} which can be executed to retrieve all

* documents matching the value of this facet.

*/

Query getFacetQuery();

}getFacetingName() and getFieldName() are returning the facet request name and the targeted document

field name as specified by the underlying FacetRequest. For example "Example 5.26, “Creating a discrete faceting request”"

that would be labelFacetRequest and label respectively.

The interesting information is provided by getValue() and getCount().

The former is the actual facet/category value, for example a concrete record label

like Universal. The latter returns the count for this value. To stick with the example again, the

count value tells you how many Cds are released under the Universal label. Last but not least,

getFacetQuery() returns a Lucene query which can be used to retrieve the entities counted in this

facet.

A common use case for faceting is a "drill-down" functionality which allows you to narrow your

original search by applying a given facet on it. To do this, you can apply any of the returned

Facet instances as additional criteria on your original query via FacetSelection. FacetSelection

is available via the FacetManager and allow you to select a facet as query criteria (selectFacets),

remove a facet restriction (deselectFacets), remove all facet restrictions (clearSelectedFacets) and

retrieve all currently selected facets (getSelectedFacets). Example 5.30, “Restricting query results via the application of a FacetSelection”

shows an example.

Example 5.30. Restricting query results via the application of a FacetSelection

// create a fulltext query

Query luceneQuery = builder.all().createQuery(); // match all query

FullTextQuery fullTextQuery = fullTextSession.createFullTextQuery( luceneQuery, clazz );

// retrieve facet manager and apply faceting request

FacetManager facetManager = fullTextQuery.getFacetManager();

facetManager.enableFaceting( priceFacetingRequest );

// get the list of Cd

List<Cd> cds = fullTextQuery.list();

assertTrue(cds.size() == 10);

// retrieve the faceting results

List<Facet> facets = facetManager.getFacets( "priceFaceting" );

assertTrue(facets.get(0).getCount() == 2)

// apply first facet as additional search criteria

FacetSelection facetSelection = facetManager.getFacetGroup( "priceFaceting" );

facetSelection.selectFacets( facets.get( 0 ) );

// re-execute the query

cds = fullTextQuery.list();

assertTrue(cds.size() == 2);Per default selected facets are combined via disjunction (OR). In case a field has multiple values,

like a potential Cd.artists association, you can also use conjunction (AND) for the facet selection.

Example 5.31. Using conjunction in FacetSelection

FacetSelection facetSelection = facetManager.getFacetGroup( "artistsFaceting" );

facetSelection.selectFacets( FacetCombine.AND, facets.get( 0 ), facets.get( 1 ) );Query performance depends on several criteria:

- the Lucene query itself: read the literature on this subject.

- the number of loaded objects: use pagination and / or index projection (if needed).

- the way Hibernate Search interacts with the Lucene readers: defines the appropriate Section 2.3, “Reader strategy”.

- caching frequently extracted values from the index: see Section 5.5.1, “Caching index values: FieldCache”.

The primary function of a Lucene index is to identify matches to your queries, still after the query is performed the results must be analyzed to extract useful information: typically Hibernate Search might need to extract the Class type and the primary key.

Extracting the needed values from the index has a performance cost, which in some cases might be very low and not noticeable, but in some other cases might be a good candidate for caching.

What is exactly needed depends on the kind of Projections being used (see Section 5.1.3.5, “Projection”), and in some cases the Class type is not needed as it can be inferred from the query context or other means.

Using the @CacheFromIndex annotation you can experiment different kinds of caching of the main

metadata fields required by Hibernate Search:

import static org.hibernate.search.annotations.FieldCacheType.CLASS;

import static org.hibernate.search.annotations.FieldCacheType.ID;

@Indexed

@CacheFromIndex( { CLASS, ID } )

public class Essay {

// ...

}It is currently possible to cache Class types and IDs using this annotation:

CLASS: Hibernate Search will use a Lucene FieldCache to improve performance of the Class type extraction from the index.

This value is enabled by default, and is what Hibernate Search will apply if you don’t specify

the @CacheFromIndex annotation.

ID: Extracting the primary identifier will use a cache. This is likely providing the best performing queries, but will consume much more memory which in turn might reduce performance.

Note

Measure the performance and memory consumption impact after warm-up (executing some queries): enabling Field Caches is likely to improve performance but this is not always the case.

Using a FieldCache has two downsides to consider:

- Memory usage: these caches can be quite memory hungry. Typically the CLASS cache has lower requirements than the ID cache.

- Index warm-up: when using field caches, the first query on a new index or segment will be slower than when you don’t have caching enabled.

With some queries the class type won’t be needed at all, in that case even if you enabled the CLASS field cache, this might not be used; for example if you are targeting a single class, obviously all returned values will be of that type (this is evaluated at each Query execution).

For the ID FieldCache to be used, the ids of targeted entities must be using a TwoWayFieldBridge (as

all built-in bridges), and all types being loaded in a specific query must use the field name for the

id, and have ids of the same type (this is evaluated at each Query execution).